It Gets The People Going

July saw two substantial instances of cultural provocation in the United States that are worth talking about—Ari Aster’s 2020-inspired film Eddington and a marketing campaign for American Eagle featuring Sydney Sweeney. The movie is a satirical look at major events of that summer—particularly Covid and the Black Lives Matter protests—that amounts to a ‘look how crazy both sides are’ thesis. The advertisements feature the tagline Sydney Sweeney has great jeans, which is certainly a choice to make as the politics of the country have hurdled into white supremacist authoritarianism.

While I have plenty to say with regards to both, I’m trying not to fall into the trap of actually getting involved in the discourse around either—because that is the sole point of both.

Provocation as an engine for creative expression is not without merit. Ai Weiwei’s Dropping A Han Dynasty Urn is a perfect example of how art can be provocative while also being targeted and inspiring. It’s shocking in a way that fosters curiosity, leaving the audience to ask questions.

When entertainment (or, worse, advertising) enters the fray of trying to provoke a reaction, it often misses the mark because it punches down in order to stir debate or outrage. It is vying for attention instead of posing a question about a larger issue in the world because it is trying to sell something. What is frustrating about Eddington and the ad campaign is that they’re both designed as rage-bait for sensitivity about the value of human equality as an idea. The film makes light of race-based protests and the ads play on the words of eugenics. Despite rampant displays of fascist behavior by people in power, these cultural entities are siding with the ideologies of the fascists.

It’s unsurprising that capitalism would push entertainers and advertisers deeper into right-wing values, because targeting the powers that be comes with real risk. (It is notable that despite being a movie about the controversies and politics of 2020, there is not a single reference to MAGA or Donald Trump.) While it’s more predictable that something as soulless as an ad campaign would indulge in controversy to sell clothes, it’s disheartening to see these pillars of cultural discourse continue to drag the Overton window still further to the right.

On Display

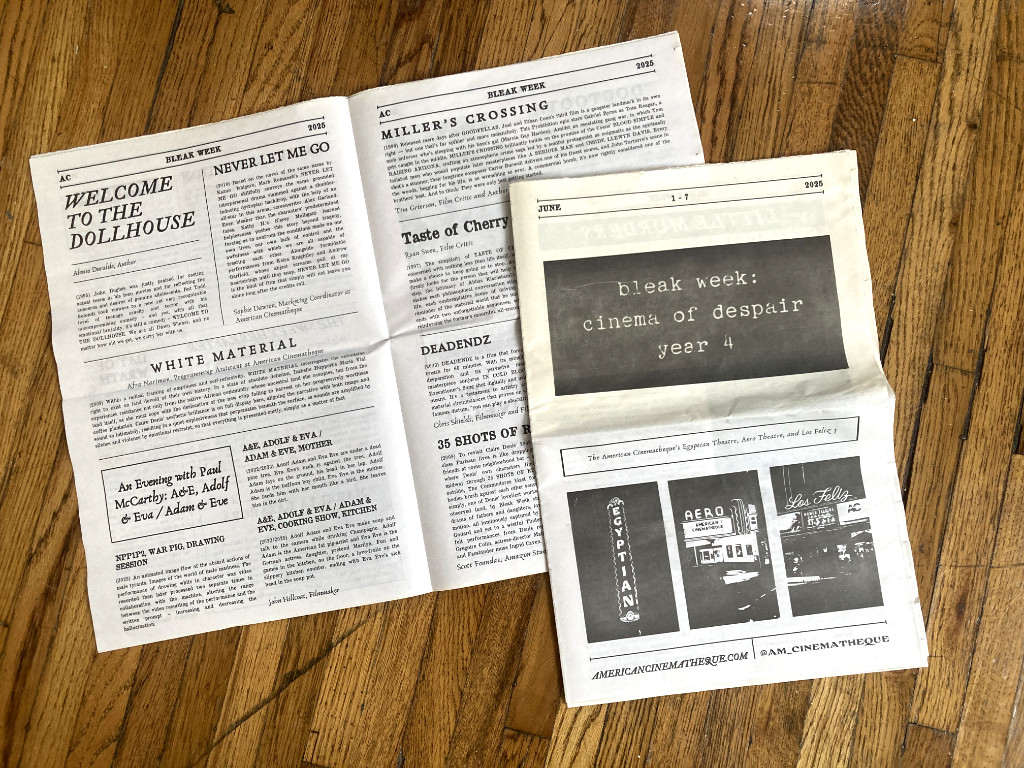

The month of June began with Bleak Week here in Los Angeles—a film festival celebrating ‘the Cinema of Despair’ put on by the American Cinematheque. Fifty-five movies played across three screens in seven days, all curated to the theme of melancholy. Ironically, it’s a pretty good time.

Bleak Week newspaper

This year, the festival guide given out at every screening took the form of a twenty-page newspaper. The publication was filled with write-ups to every movie being shown in LA, as well as a brief summary of the films being shown in other cities now that the festival has gone international. It’s a nice way to package the entire event into one space—although it is sad to see the newspaper as a form of media reduced to nostalgic giveaways.

Over the past two decades there have been many conversations about the demise of legacy media and what that means for journalism and its economic infrastructure. Advertising revenue and employment opportunity—or lack thereof—were paramount subjects. In all the discourse though, I never read much on what it actually means for people, as a society, to transition from reading the news on the page to the screen—and what it means to have an algorithm, rather than editors, feed that information to you.

NYT Front Pages

When Barack Obama was elected president, it was the first time since 9/11 that The New York Times displayed a headline using a 96-point, all-caps typeface centered on the page—and only the fourth time in history that this particular design decision was used. It’s a way for the paper to convey This is a day to remember.

Personally, I don’t care much for the Times but I can recognize the importance of having a visual hierarchy to history. Media institutions are one thing, primarily a concern of business—but there is a broader, societal loss when it comes to the decline of tangible media as a format. The companies that control the digital environment seem to remain unconcerned with how they deliver information to the masses and what impact that has on the very concept of society.

Now the main website for the Times still delivers information in a decent structure—however that structure is dependent upon what device the user is browsing the internet with. Depending on which website you ask, the mobile market share differs. However, it’s clear that smartphone browsing is only increasing a rather dominant position in web access. So what?

It’s simply an interesting problem about the concept of social fabric. If, as a society, we all individually receive different news feeds that equivocate our personal interests with stories of mass importance, where headlines are all the same size and there’s no differentiation between opinion and journalism, between fashion and politics, then it will be up to each individual to discern what is important.

This is a fundamental issue at a societal level—it’s not necessarily an uninformed public, but an increasingly fractured one. It’s impossible to imagine exactly how this would play out in terms of social unrest or breakdowns, but I think looking around at the state of things in the US makes it pretty obvious we’re finding out.

No, I don’t think the world is falling apart because newspapers started going out of business. But I do believe they represented an idea of the importance of considering what it means to deliver news and opinion to the public, both in content and design. Information is power and, intentionally or not, today’s technology leaders are woefully inept when it comes to the responsibility of broadcasting that information to the public.

Individualism and personal liberty are subjective topics in the debate about governance in the United States, but this seems to be the technological representation of those concepts—where now it’s all up to each person to decide for themselves what is worth paying attention to, what matters, and what to believe. I think we’re seeing the results of this kind of social experiment in the seats of power now.